When we design our customer experience, we typically focus on the touch points, moments of truth or my favourite moments of need. Whatever we choose to call them, these are the moments when the customer enters into contact with our service delivery system.

When we design our customer experience, we typically focus on the touch points, moments of truth or my favourite moments of need. Whatever we choose to call them, these are the moments when the customer enters into contact with our service delivery system.

Typically (but not exclusively) the contact takes one of two forms: a human touch point or a mechanical/technical touch point, like a website, a check-in console or even an airplane seat. These are important moments that combined make up the full customer experience.

As I argued in my previous blog post, the human touch points have the highest potential to create the emotional connection that is crucial in our efforts to build loyalty, but they also carry the highest risk. If our human element does not deliver, it can be much worse than an automated experience. The mechanical touch point can generally be engineered to be emotionally neutral but rarely produces something that makes your heart sing. I recently checked in to one of these fully automated hotels. It was late, I was driving and just needed a bed for a few hours. All the automation worked, but I felt terribly lonely, with no human interaction whatsoever. There was nothing wrong with the product. But there was also nothing in that experience that would entice me to do it again or tell my friends (positively) about it.

The front line employee makes or breaks it

Our front line employee has the power to make or break the experience for our customer and if we want to make sure that our customer has the best possible experience, we need to make sure that our employee experience is the best possible. Sounds so evident, but that is not always what I observe out there.

So how do we design a great employee experience?

The starting point is behaviour.

When you think about your customer experience, your dream scenario is that your employee does ‘something’ that will make the customer feel appreciated, valued, looked after etc. This is why a lot of companies invest time and effort into training their staff to do certain things in a certain way and that is great. But it only takes us halfway to where we need to be. Because when our staff does things right, we only score 3-3,5 on a satisfaction scale of 1-5. The reason is that from a customer point of view, good is the expected level. You are not surprising them by being good, that is what they expect, and anyway most of your competitors are also ‘good’ otherwise they would not have even been in the game.

So in order to take the experience beyond the 3.5, we need to make an emotional connection. In practical terms, that means that the frontline staff need to invest a bit of themselves in the transaction. They will need to be flexible and adapt to each interaction and add to that interaction what they think would be meaningful to exactly this customer situation, be empathetic. It is not enough to say: ‘have a nice day’. That is not much better than the voice at the end of the escalator at the airport that says: Watch your step… watch your step… watch…

What drive positive service behaviours beyond just mechanically doing things right?

Motivation drives behaviour.

Motivation, engagement, mindset, call it what you like. But whatever you call it, let’s agree that it is some form of inner drive. The best service employee wants to do this. They enjoy being engaged and that is driven by how they feel.  What influences how they feel?

What influences how they feel?

The two primary drivers of how we feel on the job are: The culture that we are part of and the systems we are working with.

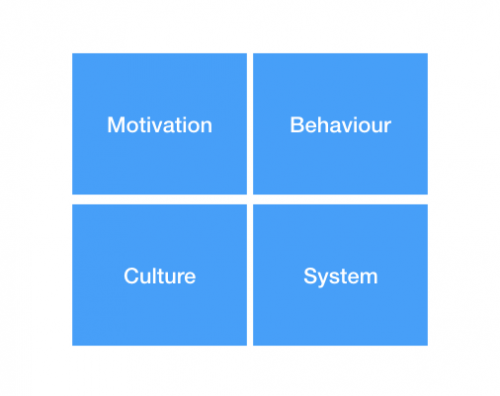

When we put all this together, we have the consultant’s favourite 2×2 matrix, but this one is a bit different because it is actually a very simple version of Ken Wilbers four quadrants in Integral Theory.

These four quadrants are interdependent. Change something in one and you affect the other three. If they become unbalanced in the sense that what is going on in one quadrant is not congruent with what we would like to see in another quadrant, then the ‘whole ‘ is not functioning optimally.

A simple example

A CEO called me to work with his group of middle managers. “They are not a team, they do not collaborate with each other and it is driving me nuts,” he said. “Can you please work with them and make that happen?”. So I asked him “What kind of remuneration system do they have?” Oh, he said, ” They get a handsome salary and they can earn a substantial individual bonus depending on how their department performs.”

Game over. As long as he maintains this ‘system’ of remuneration’, the ‘motivation’ for each of them is to do their best in they own department. There is no reason for them to collaborate. If he then further reinforces this by very strictly follow up on individual department performance, it just makes things even worse.

Understand the employee perspective through the 4 lenses

If you start analysing your service business using these four lenses, you very quickly start uncovering all sorts of things that are not congruent and therefore counter productive. The obvious ones are often in the ’System’ category. ‘Process’ or ways of working that are frustrating for front line employee but that nobody has done anything about. These we can often flesh out using Service Design tools like employee journey maps.

But the less obvious sources of disengagement come from the culture box and is typically related to what kind of psychological environment the supervisor and the supervisor’s boss is creating. As I have written about before here, culture beats strategy, always. We will take a closer look at that next week.

This spring we ran a series of blog posts around development, developing yourself and others. We have collected and edited those blog posts into a simple e-book that you can download below if you would like to explore this subject further.

This spring we ran a series of blog posts around development, developing yourself and others. We have collected and edited those blog posts into a simple e-book that you can download below if you would like to explore this subject further.